Does Insomnia Cause PTSD?: A Multi-Directional Treatise on Causality

Where This Topic Stands Today

New research reveals that 84% of chronic insomnia patients have trauma histories and over half show PTSD symptoms, but the relationship isn’t as simple as cause and effect. The truth may be more disturbing – and more hopeful – than we thought.

Maria stared at the ceiling for the 108th night. She knew the exact count because she’d started tracking when the insomnia began three years ago. What started as occasional sleeplessness after her divorce had morphed into something far more sinister. Now she jumped at car doors slamming, felt her heart race in crowded spaces, and found herself reliving the worst moments of her marriage over and over during those endless dark hours.

Her sleep doctor diagnosed chronic insomnia. Her therapist suspected PTSD. But which came first? And does it even matter?

A groundbreaking French study published in Frontiers in Sleep suggests this question haunts more people than we ever realized. Researchers found that an astonishing 83.7% of chronic insomnia patients had experienced traumatic events – far higher than the 70% seen in the general population. Even more striking, over half showed symptoms of PTSD, compared to just 3.9% of typical French adults.

But here’s the kicker: none of these insomnia patients had ever been diagnosed with PTSD. Their trauma symptoms were hiding in plain sight, masquerading as sleep problems.

The Case for Trauma-Induced Insomnia

The traditional view seems obvious: traumatic experiences disrupt sleep. Combat veterans wake up screaming from nightmares. Accident survivors often struggle to quiet their minds at bedtime. Abuse survivors feel unsafe in the darkness.

This pathway has solid biological backing. Trauma triggers the body’s alarm system – the sympathetic nervous system – into a state of hypervigilance. The brain literally can’t shut down because it’s constantly scanning for danger. Heart rates stay elevated, stress hormones flood the system, and the delicate neurochemical dance required for sleep gets completely disrupted.

Dr. Emily Belleau, a leading trauma researcher, has shown that sleep disturbances often appear within days of traumatic events. The brain’s fear centers – particularly the amygdala – become overactive, while the prefrontal cortex that usually helps us feel safe and calm becomes suppressed.

Clinicians with Sleep Recovery regularly see this pattern. Take Robert, a 34-year-old construction worker who came to the program six months after a workplace accident. He’d always been a solid sleeper until a crane malfunction nearly killed him and two coworkers.

“After the accident, bedtime became torture,” Robert recalls. “Every time I closed my eyes, I heard the metal screaming, felt the ground shake. My body knew sleep meant vulnerability, and it wasn’t having it.”

Robert’s case illustrates the classic trauma-to-insomnia pathway. A specific traumatic event created lasting changes in his brain’s threat-detection system, making sleep – a naturally vulnerable state – feel dangerous.

Within three weeks of the accident, Robert had developed textbook chronic insomnia. Within two months, he was experiencing hypervigilance episodes, avoiding construction sites, and showing irritability that strained his marriage. The sleep disruption seemed to amplify every other trauma symptom.

The Revolutionary Alternative: Insomnia-Induced Trauma

But what if we’ve been looking at this backwards? What if chronic insomnia itself can create trauma responses in people who have never experienced traditionally traumatic events?

This idea sounds radical until you consider the neuroscience. Sleep deprivation is literally a torture technique because of how profoundly it affects the brain and body. Extended periods without proper sleep create many of the same neurobiological changes seen in trauma survivors.

Chronic insomnia floods the body with stress hormones, impairs emotional regulation, and creates a state of constant physiological arousal that mirrors PTSD. The insomnia experience itself – lying awake night after night, feeling helpless and out of control – can become genuinely traumatic.

Consider the research showing that sleep-deprived individuals have enlarged, hyperactive amygdalas and reduced prefrontal cortex activity – the exact brain pattern seen in trauma survivors. After months or years of chronic insomnia, the brain literally looks traumatized on imaging scans.

Case Study: Jennifer B.

Jennifer, a 42-year-old accountant, experienced this firsthand. Her insomnia began during a stressful period at work, but continued long after the project ended. No identifiable trauma in her past, no major life disruptions – just persistent, maddening sleeplessness.

“People kept asking what I was worried about, but I wasn’t worried about anything specific,” Jennifer explains. “The insomnia itself had become the problem. I’d lie there feeling trapped in my own body, helpless, like something terrible was happening to me every single night.”

After two years of chronic insomnia, Jennifer began experiencing symptoms that looked remarkably like PTSD. She developed agoraphobia around bedtime, panic attacks when she saw her bedroom, and intrusive thoughts about sleepless nights during the day. Her sleep problems had created their own trauma response.

Through Sleep Recovery’s brainwave entrainment program, Jennifer’s brain learned to produce healthy sleep patterns again. Remarkably, as her sleep improved, the trauma-like symptoms disappeared completely – suggesting they were indeed secondary to the sleep disruption rather than caused by separate traumatic events.

The Third Possibility: Shared Vulnerability

Recent neuroscience research suggests a more complex picture. Some people may have underlying neurobiological vulnerabilities that make them susceptible to both trauma reactions and sleep disorders. Rather than one causing the other, both conditions might stem from the same source.

This “common pathway” theory focuses on the brain’s stress-response systems. People with certain genetic variations, early life experiences, or neurochemical imbalances might be predisposed to developing either condition when faced with stressors that wouldn’t affect others.

The French study supports this possibility. Researchers found no clear temporal relationship between trauma timing and insomnia onset. Some patients developed sleep problems immediately after traumatic events, others years later, and some seemed to have sleep issues that preceded their trauma symptoms entirely.

Mark S.

Mark’s story illustrates this complex relationship. A 38-year-old teacher, he’d experienced mild sleep problems since college but functioned normally for years. Then came a series of moderately stressful events – job changes, moving, his father’s illness – that wouldn’t typically cause PTSD in most people.

“Looking back, I think my brain was already vulnerable,” Mark reflects. “The sleep problems were like a crack in the foundation. When life stress hit, everything just collapsed.”

Mark developed both severe insomnia and trauma-like symptoms nearly at the same time. His response to everyday stressors became disproportionately intense, suggesting an underlying sensitivity that affected both his sleep regulation and stress processing systems.

After completing Sleep Recovery’s program, Mark not only sleeps better but also handles stress more effectively. “Fixing my sleep seemed to fix my brain’s entire stress system,” he notes. “I can deal with normal life challenges now without falling apart.”

The Neuroscience of Bidirectional Trauma

The most compelling explanation may be that trauma and insomnia create self-reinforcing cycles that make causality nearly impossible to determine. Each condition makes the other worse, creating escalating feedback loops that can persist long after initial triggers are gone.

Sleep disruption impairs the brain’s ability to process and integrate traumatic memories. During healthy REM sleep, the brain essentially “edits” emotional memories, reducing their intensity while preserving important information. When sleep is disrupted, traumatic memories remain raw and intrusive.

Simultaneously, trauma symptoms like hypervigilance and anxiety make quality sleep nearly impossible. The brain remains on high alert, interpreting normal sleep sensations – the feeling of consciousness fading, temporary paralysis during REM sleep – as potential threats.

This conundrum creates what researchers call “mutually maintaining factors.” Poor sleep makes trauma symptoms worse, while trauma symptoms make sleep problems worse. Over time, these cycles can become self-sustaining even if the original trigger – whether trauma or sleep disruption – is removed.

The Hidden Epidemic

The French study’s most concerning conclusions may be that none of the insomnia patients had been pre-screened for unresolved trauma, despite over half showing apparent symptoms.

Sleep medicine has traditionally focused on identifying physical causes of insomnia, such as sleep apnea, restless legs, and circadian rhythm disorders. When these aren’t found, patients often receive generic advice about sleep hygiene or prescriptions for sleeping medications that don’t address underlying trauma responses.

David Mayen, founder of Sleep Recovery, has observed this pattern throughout his 16 years working with chronic insomnia patients. “We regularly see clients whose sleep problems are clearly connected to traumatic stress, but they’ve never been screened for trauma,” he explains. “And we see others whose trauma symptoms seem to stem from the chronic stress of severe insomnia.”

Breaking the Cycle

The encouraging news is that addressing either condition often helps both. Sleep Recovery’s brainwave entrainment approach works by retraining the nervous system’s fundamental arousal patterns – the same systems disrupted in both chronic insomnia and trauma responses.

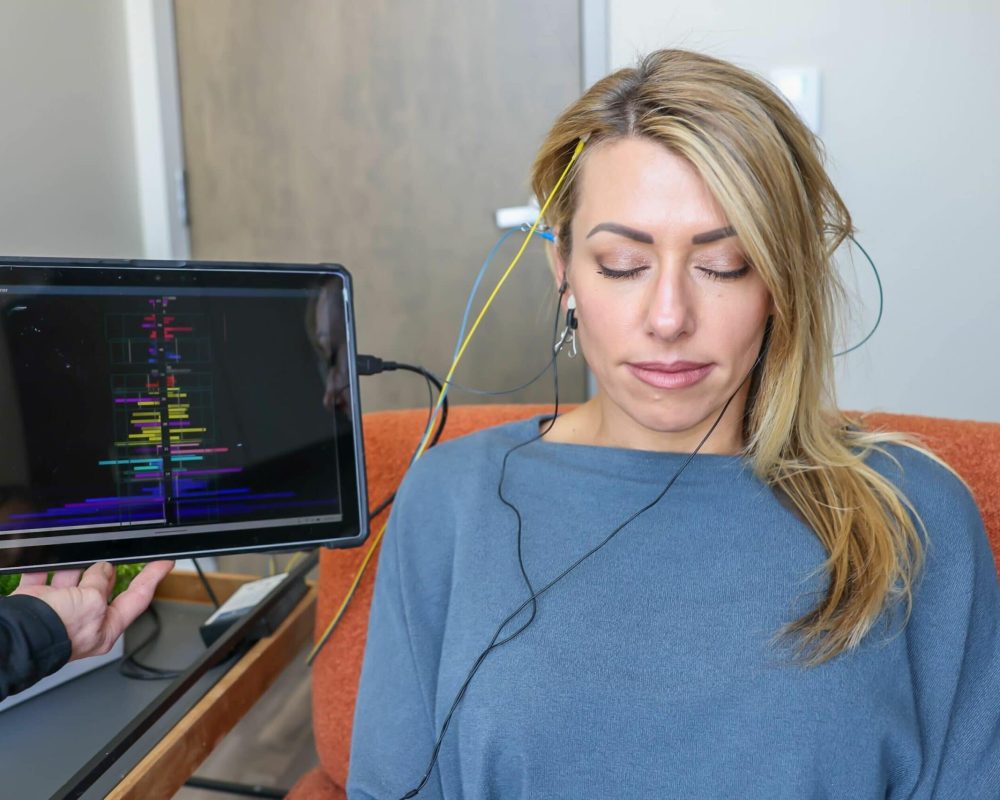

The program’s 30-minute sessions, held every other day, utilize precise audio and light frequencies to guide the brain into healthy sleep patterns. As clients’ sleep architecture improves, many also experience reduced anxiety, better emotional regulation, and decreased trauma symptoms.

“When we fix the underlying neurological dysfunction that affects sleep, we often see improvements across the board,” Mayen notes. “Better sleep seems to give the brain the resources it needs to process stress and trauma more effectively.”

Research supports this integrated approach. Studies show that trauma-focused therapies work better when combined with sleep interventions, while sleep treatments are more effective when trauma symptoms are also addressed.

The Gender Factor

The French study revealed another crucial insight: the relationship between insomnia and trauma appears to be sex-specific, with women showing much stronger correlations between trauma history, PTSD symptoms, and insomnia severity.

This finding aligns with broader research showing that women are twice as likely as men to develop PTSD and are also more prone to chronic insomnia. Hormonal factors, differences in stress response systems, and higher rates of certain types of trauma may all contribute to women’s increased vulnerability.

For treatment providers, this suggests the need for gender-sensitive approaches that recognize how trauma and sleep problems may interact differently in men and women.

Implications for Treatment

Understanding the covert relationship between emotional trauma and insomnia has profound implications for treatment. Rather than debating which came first, clinicians should assess both conditions and address them simultaneously.

Sleep centers should routinely screen for trauma history and PTSD symptoms. Mental health providers treating trauma should evaluate sleep quality and consider sleep-focused interventions. Most importantly, patients shouldn’t have to choose between addressing their sleep problems or their trauma symptoms – both need attention.

The Sleep Recovery approach exemplifies this integrated thinking. By targeting the neurobiological systems that underlie both conditions, the program often helps clients improve both sleep quality and trauma symptoms simultaneously.

Looking Forward

The chicken-and-egg question about trauma and insomnia may be the wrong question entirely. Instead of only seeking a mono-directional causality, we might better serve patients by recognizing these as interconnected conditions that require comprehensive approaches.

What matters most isn’t whether Maria’s insomnia caused her trauma symptoms or vice versa. What matters is recognizing that her sleepless nights and emotional distress are part of the same problem – one that can be addressed through treatments that work with the brain’s natural healing capacity.

For the millions of people struggling with both chronic insomnia and trauma symptoms, this perspective offers hope.

To learn more about comprehensive approaches that address both sleep and trauma symptoms simultaneously, contact Sleep Recovery at (800) 927-2339 or visit https://sleeprecovery.net.