Poor Sleep and Dementia: How Geriatric Insomnia Accelerates Alzheimer’s

Sleep problems aren’t just about feeling tired anymore. A massive wave of new research paints a terrifying picture of what happens when we don’t get proper rest, especially as we age. The latest findings show that sleep disturbances don’t just make you groggy the next day; they might accelerate your brain’s aging process and significantly raise your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

But here’s the thing that’s getting researchers excited: this connection works both ways. If poor sleep contributes to cognitive decline, fixing sleep problems might be one of the most powerful tools for protecting our brains as we age.

The Research That’s Changing Everything

Multiple longitudinal studies involving hundreds of thousands of participants are now showing clear connections between sleep problems and dementia risk. A comprehensive meta-analysis published in 2024 examined data from over 246,000 people followed for nearly a decade. The results were shocking.

People with chronic insomnia showed significantly higher rates of developing most types of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. But it gets more specific than that. The studies found that too little sleep (less than 7 hours) and too much sleep (over 8 hours) created problems, though in different ways for different age groups.

What’s interesting is that the relationship isn’t simple. Short sleep duration in younger seniors (under 70) increased dementia risk. But in older adults (70+), long sleep duration became a bigger problem, doubling the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. This finding suggests that sleep patterns might be early warning signs of brain changes that are already happening.

Dr. Michael Irwin’s research team found that sleep fragmentation, waking up multiple times at night, was particularly damaging. People who experienced frequent awakenings showed accelerated accumulation of amyloid plaques in their brains, the hallmark protein deposits associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

What Happens To Your Brain During Bad Sleep

Understanding why sleep problems lead to cognitive decline requires looking at what your brain does during healthy sleep cycles. This issue isn’t just about rest; sleep is when your brain performs some of its most critical maintenance work.

During deep sleep stages, particularly slow-wave sleep, your brain activates what scientists call the “glymphatic system.” Think of it like a nighttime cleaning crew that flushes out toxic proteins, including the amyloid and tau proteins that accumulate in Alzheimer’s disease. This cleaning process becomes less efficient when sleep gets disrupted, allowing harmful proteins to build up over time.

Proper sleep also plays a vital role in long-term memory consolidation. During REM sleep, your brain processes the day’s experiences, transferring important information from temporary storage to long-term memory. Chronic sleep disruption interferes with this process, making it harder to form new memories and potentially accelerating the memory problems that characterize early dementia.

The inflammatory response tells another part of the story. Poor sleep triggers chronic low-grade inflammation throughout your body, including your brain. This inflammation contributes to the destruction of brain cells and the formation of the protein tangles seen in Alzheimer’s disease. People with chronic insomnia often show elevated levels of inflammatory markers that correlate with faster cognitive decline.

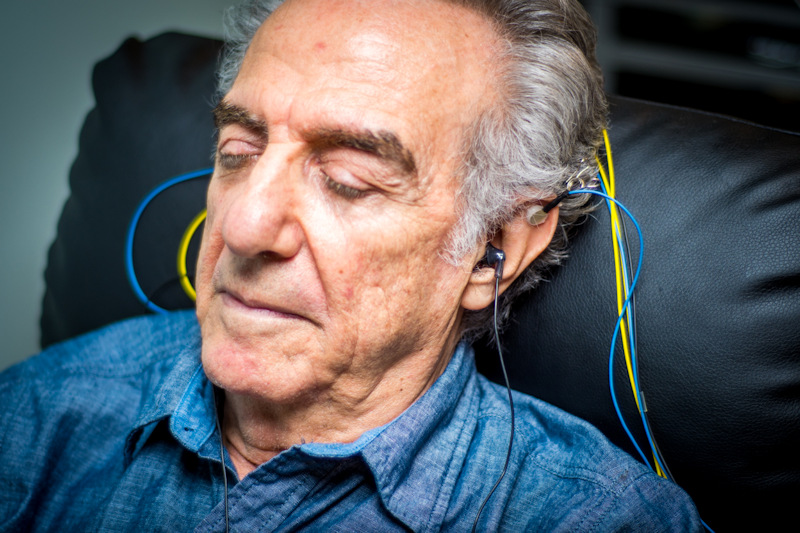

The Polysomnography Evidence

When researchers hook people up to sophisticated sleep monitoring equipment called polysomnography (PSG), the differences between healthy older adults and those developing cognitive problems become crystal clear. A recent systematic review of 28 studies using PSG found consistent patterns in people who later developed Alzheimer’s disease.

The studies also found that the severity of sleep disruption correlated directly with cognitive test scores. People with the most disturbed sleep showed the most significant impairments in memory, attention, and executive function testing.

Sleep Disorders That Raise Red Flags

Not all sleep problems carry the same level of risk for cognitive decline. Research has identified several specific sleep disorders that seem particularly dangerous for brain health.

Obstructive sleep apnea is one of the most concerning conditions. When people stop breathing repeatedly at night, it deprives the brain of oxygen while fragmenting sleep. Studies show that untreated sleep apnea can accelerate cognitive decline by several years. The fortunate news is that treating obstructive sleep apnea with CPAP therapy often improves cognitive function, especially if treatment starts before significant brain damage occurs.

Restless leg syndrome, characterized by unbearable tingling in the legs that creates an irresistible urge to move, also appears on the radar. While less studied than sleep apnea, emerging research suggests that RLS may independently increase dementia risk, possibly through its effects on sleep fragmentation and stress hormone production.

Circadian rhythm disorders, where people’s internal body clocks become misaligned with the day-night cycle, represent another concern. Shift workers and people who keep irregular sleep times show higher rates of cognitive problems as they age, suggesting that the timing of sleep may be just as important as the amount.

The Age Factor Makes Everything More Complicated

One of the most surprising findings from recent research is that the relationship between sleep and cognitive decline changes dramatically with age. This indicates that aging doesn’t just worsen everything; the patterns suggest fundamentally different processes at various life stages.

In people under 70, insufficient sleep seems to be the primary problem. These individuals who consistently sleep less than 7 hours per night show increased dementia risk, possibly because they’re not getting enough time for brain maintenance processes. The chronic sleep debt accumulates over time, contributing to the earlier onset of cognitive problems.

But the pattern flips after age 70. Excessive sleep duration (over 8 hours) becomes more strongly associated with dementia risk.

This age-related pattern has important implications for sleep recommendations. The standard advice of “7-9 hours per night” might need to be refined based on age, with older adults potentially benefiting from different targets.

Modern Sleep Recovery Approaches

Developing effective treatment modalities becomes critically important given the mounting evidence connecting sleep problems to cognitive decline. Traditional approaches focused primarily on sleep medications. However, newer research suggests that pharmaceutical solutions may not address the underlying brain wave irregularities contributing to sleep problems and cognitive decline.

Advanced sleep recovery programs now utilize brainwave entrainment technology that works directly with the brain’s electrical patterns rather than just trying to induce sleep through chemical means. This approach recognizes that healthy sleep requires properly synchronized brain wave activity across different sleep stages.

Brainwave entrainment uses precisely calibrated light and sound stimulation to guide the brain into optimal frequency patterns associated with restorative sleep. Unlike sleep medications that can interfere with natural sleep architecture, these technologies restore the brain’s natural ability to cycle through deep sleep and REM stages efficiently.

Clinical programs like Sleep Recovery have significantly improved sleep quality and daytime cognitive function using audio-visual entrainment (AVE) technology. Their approach combines multiple modalities to address the neurological basis of sleep disruption rather than just managing symptoms.

The technology works by detecting and correcting brainwave instabilities that underlie many sleep disorders. Using FDA-approved devices, these programs can help restore standard sleep patterns in as little as 30-minute sessions every other day without the side effects of long-term medication use.

The Neuroplasticity Connection

What makes sleep recovery approaches particularly promising is their basis in neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize and form new neural connections throughout life. Research shows that the brain remains remarkably adaptable even in older adults, meaning that interventions targeting sleep quality can potentially reverse some of the damage associated with chronic sleep deprivation.

Neuroimaging studies have shown that people who improve their sleep quality through non-pharmaceutical interventions often demonstrate measurable improvements in brain structure and function. Regions of brain structure responsible for both short—and long-term memory formation and executive function show increased volume and improved connectivity after sleep recovery programs.

This neuroplasticity effect may be significant for ameliorating the development of Alzheimer’s disease. By restoring healthy sleep architecture, we may enhance the brain’s natural cleaning processes, reduce inflammatory damage, and support the formation of new neural pathways that can compensate for early disease-related changes.

The timing of intervention appears crucial. Starting sleep recovery programs before a significant cognitive decline occurs offers the best chance for preventing or delaying dementia onset. However, even people with mild cognitive impairment can benefit from improved sleep quality, potentially slowing their rate of decline.

The Technology-Assisted Future

Emerging technologies are making sophisticated sleep interventions more accessible than ever before. Portable devices can now monitor sleep patterns in home environments and provide real-time feedback to optimize sleep quality.

Advanced systems combine multiple sensory modalities—light, sound, and even tactile stimulation—to guide the brain through optimal sleep cycles. Targeted technologies can be customized based on individual brain wave patterns and adjusted automatically based on response monitoring.

The rapid development of artificial intelligence allows these systems to learn from individual responses and refine their protocols over time. This calibrated approach is more effective than one-size-fits-all interventions for addressing the complex relationship between sleep and cognitive health.

Professional sleep recovery programs now utilize combinations of these technologies and personal coaching to address the technical and behavioral aspects of sleep improvement. This innovative approach recognizes that sustainable sleep recovery requires brain function and changes in daily habits.

What This Means For Prevention

The research linking sleep disturbances to Alzheimer’s risk carries profound implications for prevention strategies. Unlike many risk factors for dementia—such as age, genetics, or family history—sleep problems are largely modifiable through appropriate interventions.

This modifiability makes sleep health one of the most promising targets for preventing or delaying cognitive decline. The evidence suggests that addressing sleep problems early, ideally before significant cognitive symptoms appear, offers tremendous potential for maintaining brain health throughout aging.

Healthcare providers are beginning to recognize sleep quality as a vital sign that should be assessed regularly in older adults. Early identification of sleep disorders allows for intervention before they contribute to irreversible brain changes.

The cost-effectiveness of sleep interventions compared to dementia care makes this approach attractive from a public health perspective. Preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset by even a few years could dramatically reduce the societal burden of this devastating condition.

Individualized Actions

Advanced intervention approaches make sense for people with chronic sleep problems who haven’t responded to basic sleep hygiene measures. Technology-assisted programs, specialized cognitive behavioral therapy, or medical evaluation for sleep disorders may be necessary.

Maintaining overall brain health through exercise, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation works synergistically with sleep improvement efforts. Good sleep and an active lifestyle provide the strongest protection against cognitive decline.

Looking At The Evidence

The relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease represents one of the most critical developments in dementia research in recent years. The evidence consistently shows that sleep problems aren’t just symptoms of aging or early cognitive decline—they’re active contributors to the disease process.

This understanding changes the focus from simply managing sleep problems to recognizing them as critical intervention points for preventing cognitive decline. This causal relationship between sleep and brain health means that improving sleep quality can slow or stop the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

The availability of effective, non-pharmaceutical interventions makes this particularly encouraging. Unlike many aspects of aging and disease risk, sleep problems can often be addressed through appropriate technology and behavioral interventions.

The challenge now rests in cultivating awareness among healthcare providers and the general public about the importance of sleep health for cognitive preservation. Too many people still view sleep problems as minor inconveniences rather than grave threats to long-term brain health.

The Bottom Line

Poor sleep isn’t just making you tired—it might be actively damaging your brain and raising your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The great news is that this connection works both ways: improving sleep quality can potentially protect your cognitive health as you age.

Research shows that sleep disturbances contribute to the brain changes associated with dementia, while restoring healthy sleep patterns may help prevent or slow cognitive decline. Modern technology-assisted approaches offer new hope for people who haven’t found success with traditional sleep improvement methods.

The key insight is that sleep problems should be addressed proactively, especially in people over 50. Rather than accepting poor sleep as an inevitable part of aging, we now understand it as a modifiable risk factor that deserves the same attention as diet, exercise, and other health behaviors.

The choice between ignoring sleep problems and taking action to address them may ultimately determine whether you maintain sharp cognitive function throughout your later years or face the devastating progression of dementia. That choice seems pretty straightforward, given what we know about the sleep-memory connection.