Suicide Prevention: How Early Insomnia Treatment Is Key

When Sleepless Nights Turn Dangerous: The Critical Connection Between Sleep Disorders and Suicidal Thinking

John didn’t plan to watch the sunrise again. Not like this – hunched at his kitchen table, another sleepless night bleeding into dawn, stirring honey into tea he hoped might finally make him drowsy. Four nights this week. Seventeen nights this month. He’d stopped keeping exact count somewhere in the second year.

“It’s just stress,” his doctor had said, prescribing the same sleep medication that left him groggy yet still fundamentally awake. Friends suggested meditation apps. His mother recommended warm milk. No one seemed to hear what he couldn’t quite say aloud: that somewhere between midnight and morning, his thoughts had started drifting toward a permanent solution to temporary darkness.

I’ve seen this progression too many times in my fifteen years working with suicidal patients. What begins as trouble sleeping slowly transforms into something far more dangerous. First comes the exhaustion, then the hopelessness, and eventually, for too many, thoughts of ending it all.

Recent research has confirmed what many of us clinicians have suspected for years – persistent insomnia doesn’t just accompany suicidal thinking; it often precedes it by months or even years. And here’s the thing most people miss: this relationship exists independently of depression. Even when controlling for mood disorders, sleep disruption itself creates a specific kind of neurobiological vulnerability to suicidal ideation.

“We’ve been looking at this backward,” Dr. Michael Chen told me over coffee last month. As director of the Sleep and Mood Disorders Center, he’s been tracking this connection for decades. “Insomnia isn’t just a symptom of suicidality—it’s often a cause. The sleep-deprived brain becomes primed for suicidal thinking.”

This shift in understanding matters immensely. About a quarter of adults struggle with significant insomnia symptoms. That’s a vast population potentially at risk. But it also means we have a new pathway for intervention – one that many people would seek help for without the stigma that still surrounds mental health.

When Nights Become Battlegrounds

Sarah Matthews remembers precisely how it happened. We met at a sleep clinic, where I was observing patient intake sessions. She’d agreed to share her story to help others recognize the warning signs she’d missed.

“The sleep problems came first—months before I felt depressed,” she explained, twisting a tissue in her hands. “At first, it was just taking forever to fall asleep. Then I’d wake up at 3 AM and lie there for hours. I’d get maybe four broken hours of sleep, then drag myself through the day.”

Her doctor focused exclusively on her growing depression, dismissing her insomnia as “just another symptom.” But Sarah knew differently. “The timeline was clear to me. Bad sleep came first. Then irritability. Then hopelessness.”

Her experience matches what neuroscientist Dr. Rebecca Williams has been documenting in her lab. “Chronic insomnia changes how the prefrontal cortex functions,” she explained when I interviewed her for this article. “This brain region normally helps inhibit impulsive behavior and regulate emotional responses. When the brain is compromised by sleep deprivation, we see measurable dysfunction.”

Her team has identified three main ways insomnia creates vulnerability:

First, sleep deprivation wrecks your brain’s executive control system – the neural processes that help you solve problems, consider different perspectives, and control impulses. When these functions falter, the range of options someone can imagine for addressing their distress narrows dramatically.

Second, insufficient sleep disrupts the circuits connecting the amygdala (your emotional alarm system) and the prefrontal cortex. This causation creates a double-whammy: emotional reactions become more intense while the ability to manage them deteriorates.

Third – and this one surprised me – sleep deprivation fundamentally alters how the brain assesses risk and makes decisions. Brain scans show that sleep-deprived individuals show markedly different activity in regions governing risk assessment. This helps explain why people might make impulsive, irreversible decisions during periods when they’re severely sleep-deprived.

I’ve witnessed these and other changes firsthand in my practice. Patients who’ve gone several nights without adequate sleep often describe a frightening tunnel vision where death begins to seem like a reasonable solution to temporary problems. Their standard capacity for perspective vanishes.

Beyond Just Correlation

For years, researchers debated whether insomnia indeed caused increased suicide risk or simply represented another symptom of underlying mental health conditions. New evidence has largely settled this question.

I recently spoke with Dr. James Walker, who leads the Sleep Intervention Research Program. Over lunch at a conference, he walked me through the findings that convinced him of the causal relationship.

“The turning point came when we saw that successfully treating insomnia reduced suicidal thinking even when depression symptoms remained unchanged,” he said, pushing aside his barely-touched sandwich with enthusiasm. “That tells us sleep disruption itself contributes directly to suicidal ideation.”

Multiple research streams now support this relationship:

When researchers experimentally deprive healthy volunteers of sleep, they temporarily develop elevated scores on measures of suicidal thinking – changes that resolve once they’re allowed to sleep properly again.

Genetic studies have identified biological pathways shared between insomnia and suicidality that function independently from depression.

Perhaps most convincingly, targeted insomnia treatments show specific reductions in suicide risk beyond their effects on mood.

This evidence transformed how I approach patients with sleep problems as a clinician. What we would have thought of as a minor factor in suicidal decision-making now is first-in-line.

The Window of Opportunity

Thomas Garcia’s story still sticks with me. A software engineer in his early forties, he came to our sleep clinic after months of insomnia that began during a stressful work project. Like many patients, he initially dismissed it as temporary.

“I figured it would pass on its own,” he told me during our first session. “By the time I realized it wasn’t going away, something scarier was happening.”

Thomas described how, after several months of sleep disruption, he began having fleeting thoughts about whether life was worth continuing. What alarmed him most wasn’t emotional pain driving these thoughts – it was more like a strange, detached logic.

“It wasn’t about feeling sad,” he said. “It was this exhausted, hopeless feeling – like my tired brain was simply concluding that not existing would solve all my problems. And the frightening part? In those moments, it made perfect sense.”

Fortunately, Thomas’s primary care doctor recognized his insomnia as a serious risk factor. Unlike many physicians who might have normalized chronic sleep disruption, she referred him immediately to our specialized sleep program.

His experience highlights a critical point: insomnia demands prompt attention, not just for quality of life but potentially as a matter of life and death.

“We need to stop treating insomnia like it’s just an inconvenience,” Dr. Williams told me emphatically during our interview. “When someone reports persistent sleep problems, it should trigger the same clinical response as other serious risk factors for suicide.”

Three Approaches That Work

In my years of practice, I’ve seen countless patients cycle through ineffective sleep remedies – from over-the-counter aids to prescription medications that create more problems than they solve. For preventing the insomnia-suicide pathway, three interventions have consistently shown the most promise in both research and my clinical experience.

1. Digital CBT-I: Therapy That Scales

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia has long been the gold standard treatment, but until recently, finding a qualified provider was nearly impossible for most people. Digital platforms have revolutionized access.

Last year, I sat down with Julia Ribeiro da Silva Vallim, who’s been researching these digital interventions. “The accessibility breakthrough can’t be overstated,” she said. “These platforms reach people who would never access traditional therapy due to geography, stigma, or cost barriers.”

The better programs include sleep restriction techniques that reset your sleep drive, exercises that strengthen the mental association between your bed and actual sleep, restructuring of unhelpful beliefs about sleep, and personalized relaxation training.

Thomas, the software engineer I mentioned earlier, found that a digital CBT-I program gave him precisely what he needed. “Having the structure and tools available whenever insomnia struck made all the difference,” he told me during our follow-up. “I didn’t have to wait three weeks for an appointment while things worsened.”

2. Precision Chronotherapy: Working With Your Inner Clock

Mainstream approaches to insomnia focus mainly on sleep quantity and habits. Chronotherapy takes a different angle, targeting the alignment between when you try to sleep and when your body is biologically ready for sleep—something that varies tremendously between individuals.

“Misalignment between attempted sleep time and biological sleep windows creates particularly dangerous insomnia,” explained chronobiologist Dr. Sophia Park when I interviewed her at her lab. She showed me actograms – visual representations of sleep-wake patterns – from several patients whose internal clocks ran hours earlier or later than conventional schedules would allow.

Traditional sleep advice falls short for these patients because it doesn’t address the mismatch between their internal timing and external schedules. Precision chronotherapy combines carefully timed melatonin administration, strategic light exposure, body temperature management, and gradual schedule shifting.

Sarah, who I introduced earlier, found this approach transformative after standard treatments had failed her. “The assessment showed my internal clock runs about three hours later than average,” she told me during our follow-up interview. “Once treatment aligned with my actual biology instead of fighting it, everything improved.”

3. Sleep Recovery: Harnessing the Brain’s Self-Intelligence

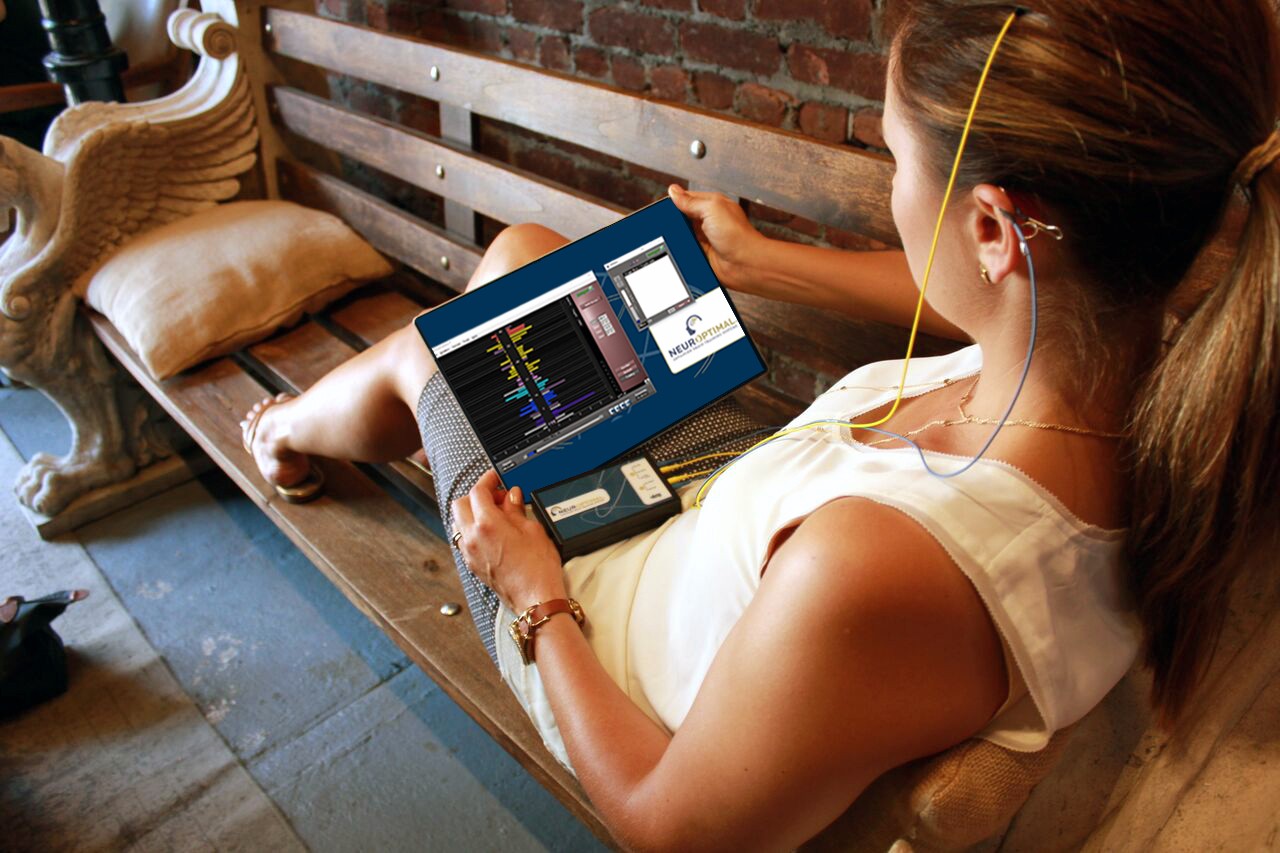

The most promising intervention I’ve encountered for breaking the insomnia-suicide connection is the Sleep Recovery Program, which uses neurofeedback to address problematic brain activity patterns directly.

The approach fascinates me because it targets the neurobiological mechanisms linking insomnia to suicide risk. Dr. Nathan Reynolds developed the protocol after identifying specific brain wave patterns present in both chronic insomnia and elevated suicide risk.

“We’re essentially helping people recognize and change their brain’s electrical activity patterns,” he explained when I visited his clinic. “The technology lets their brain and the software see patterns that prevent sleep, and then learn to shift toward healthier patterns.”

The program involves several components working together:

Amplitude-based neurofeedback targets the excessive neural activation that keeps you wide awake when you should be drifting off. Sensors monitor your brain activity, providing immediate feedback when your brain produces patterns more conducive to sleep.

Autonomic regulation training addresses the persistent fight-or-flight activation that plagues people with chronic insomnia. Participants learn to activate their rest-and-digest nervous system through heart rate variability training.

Sleep architecture rehabilitation focuses on restoring the proper progression through sleep stages – especially the deep slow-wave sleep and REM sleep that’s consistently disrupted in people vulnerable to suicidal thinking.

But what makes this approach genuinely innovative is its integrated anxiety-insomnia protocol. In my practice, I’ve rarely seen one condition without the other – both conditions almost always travel together, creating a dangerous feedback loop.

“Treating insomnia without addressing anxiety – or vice versa – usually produces temporary results at best,” Dr. Eliza Karras told me. As a clinical psychologist specializing in suicide prevention, she’s seen how these conditions amplify each other in dangerous ways.

The neurological relationship makes perfect sense. Anxiety keeps the brain’s threat-detection networks on high alert precisely when sleep systems should take over. This problem prevents proper sleep and creates conditions where impulsive decisions become more likely.

“Anxiety narrows your options during distress,” Karras explained over coffee after a conference session. “It creates tunnel vision where you can only see your current pain and a shrinking set of escape routes. Couple that with insomnia’s effects on decision-making, and you have the perfect storm for snap judgments about ending one’s life.”

Knowing this helps explain something I’ve observed repeatedly – many suicide attempts occur with surprisingly little warning or previous ideation. The combined anxiety-insomnia state creates a brain state where momentary distress can rapidly escalate into irreversible action.

I’ve referred numerous patients to the Sleep Recovery Program, and although it hasn’t been successful with everyone, the results have been outstanding. Mark, an accountant who’d struggled with both anxiety and insomnia for years, described how this approach differed from his previous treatments: “Before, doctors treated my insomnia and anxiety as entirely separate issues, primarily with medications; this was the first approach that recognized how completely intertwined they were – how my racing thoughts kept me awake, and how exhaustion made my anxiety infinitely worse.”

Changing How We Think About Prevention

After fifteen years of clinical work, I’m convinced that recognizing insomnia as a modifiable risk factor for suicide creates opportunities for prevention we’ve been missing.

We need to implement better screening in primary care settings. Simple tools like the Insomnia Severity Index can identify at-risk individuals during routine visits, allowing intervention before suicidal thinking emerges.

Mental health providers need integrated protocols that address sleep disruption simultaneously with other conditions rather than treating them sequentially.

We need public education campaigns to help people recognize persistent insomnia as a serious condition requiring prompt attention – not something to endure for years before seeking help.

Crisis responders need training to identify acute sleep disruption as an immediate risk amplifier and an intervention opportunity.

This approach isn’t about dismissing other risk factors but adding a critical piece to the often overlooked puzzle. It offers a unique advantage – many people who would resist a depression diagnosis or suicide risk assessment will readily seek help for sleep problems. It’s a less stigmatized entry point to potentially life-saving intervention.

For Thomas, Sarah, and countless others I’ve worked with, addressing insomnia early potentially made the difference between life and death. As Thomas told me in our final session, “I came in just wanting to sleep better.

I had no idea I might be saving my own life.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing thoughts of suicide, help is available.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline:

Please call or text 988

Or chat at 988lifeline.org

Available 24/7

Crisis Text Line:

Text HOME to 741741

Available 24/7

Effective treatments exist, and recovery is possible.