Is Napping Harmful? The Latest Data on Daytime Shut Eye

The conventional wisdom around napping has been simple. If you’re tired during the day, a quick nap will refresh you. Mediterranean cultures have built entire schedules around the afternoon siesta. Companies have installed nap pods to boost employee productivity. The messaging is everywhere: naps are good for you.

But new research is forcing a complete rethink of this assumption. Studies tracking hundreds of thousands of people over many years are finding something troubling. Long naps, frequent naps, and naps at certain times of day are linked to higher risks of death from all causes. This doesn’t mean napping itself is dangerous. What it suggests is far more interesting and vital. The way people nap may offer a peek into underlying health problems that haven’t yet shown up elsewhere.

What the Numbers Actually Show

A massive meta-analysis published in 2024 examined 44 studies involving more than 1.8 million people. The results were striking. People who habitually napped had increased risks of multiple health problems, including death from any cause, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, and cancer. But before you swear off afternoon rest forever, the details matter a lot.

The risk wasn’t the same for everyone who napped. Duration turned out to be critical. People who napped for 30 minutes or more had a significantly higher risk of these health problems. But people whose naps lasted less than 30 minutes showed no significant increase in risk. Some studies even found that short naps of less than an hour were linked to a lower risk of early death.

A study from China following more than 20,000 people for seven years found similar patterns. Compared to people who didn’t nap at all, those who napped for 90 minutes or more had a 23% higher risk of death. But people who napped for less than 60 minutes actually had a 29% lower risk of early death. The sweet spot was short naps, not avoiding naps entirely.

Even more interesting, the timing of naps appeared to matter. A 2025 study presented at the SLEEP annual meeting used actigraphy devices to objectively track when people slept during the day, rather than relying on self-reports. They followed over 86,000 middle-aged and older adults in the UK for up to 11 years. The data challenged what sleep experts thought they knew.

Higher percentages of naps taken around noon and in the early afternoon were associated with greater mortality risk. It directly contradicts the standard advice that the ideal time to nap is early afternoon. The researchers were sufficiently surprised by this finding that they called for further research to understand why the conventional wisdom might be wrong.

Beyond timing and duration, consistency mattered too. People whose nap duration varied a lot from day to day had worse outcomes than those who napped more consistently. This variability itself signals something about unstable sleep patterns or underlying health issues.

Why Location and Culture Complicate the Picture

Here’s where things get complicated. The same behavior can mean completely different things in different contexts. In Mediterranean countries where siestas are part of the cultural norm, the health associations with napping differ from those in places where napping is less common.

Some studies from Spain and Greece have found that regular, planned siestas in cultures where they’re expected don’t carry the same health risks. In fact, in these contexts, moderate napping has been linked to better cardiovascular health. But when researchers examine habitual napping in countries where it’s not the cultural norm, such as the United States or China, the associations tend to be negative.

This data suggests that why someone naps matters as much as how long they nap. Are they napping as part of a planned daily routine in a culture that values rest? Or are they napping because they’re exhausted, sleep-deprived, or dealing with an underlying health condition that makes them excessively tired during the day?

The same nap can have completely different meanings. A planned 20-minute power nap taken by someone who got good sleep the night before is fundamentally different from a 90-minute nap taken by someone who’s chronically exhausted and can’t stay awake during the day. The first might refresh and restore. The second is a symptom of a bigger problem.

The Sleep Debt Connection

This insight leads us to what may be the most essential of all this research. Long, frequent naps often aren’t the problem themselves. They’re a warning sign pointing to poor nighttime sleep quality.

Multiple studies have found that when you combine long napping with either too little or too much nighttime sleep, the mortality risks multiply. People who napped for 90 minutes or more and also slept 8 hours or more per night had a 50% higher risk of death compared to people who didn’t nap and slept 6 to 8 hours nightly.

This pattern tells us something crucial. The issue isn’t the rest itself. The problem is that something is disrupting the normal sleep-wake cycle. The person is sleeping long hours at night but still needs extended naps during the day. Or they’re getting insufficient nighttime sleep and trying to make up for it with long daytime naps. Either way, the sleep system isn’t working correctly.

Research consistently shows that people with undiagnosed sleep disorders are more likely to be habitual nappers. Sleep apnea, for instance, fragments nighttime sleep so badly that sufferers are often desperately tired during the day despite spending plenty of time in bed. They may sleep 8 or 9 hours at night, but wake up hundreds of times due to breathing interruptions they’re unaware of. The long daytime naps are their body’s attempt to compensate for sleep that isn’t actually restorative.

Chronic insomnia creates a similar pattern. Someone might lie in bed for 8 hours but only actually sleep for 5 or 6, with the rest spent awake and frustrated. During the day, exhaustion catches up with them and they crash into long naps. But these naps often worsen nighttime insomnia by reducing sleep pressure, creating a vicious cycle.

The Hyperarousal Factor

There’s another piece to this puzzle that often gets overlooked. Many people who struggle with sleep aren’t dealing with simple sleep deprivation. They’re dealing with hyperarousal, a state in which the nervous system is stuck in high gear and can’t downshift into rest mode.

Hyperarousal shows up in multiple ways. Some people have racing thoughts that won’t quiet down. Others experience physical tension that prevents deep relaxation. Many have both. Their bodies are tired, but their nervous systems are wired, leaving them simultaneously exhausted and unable to rest fully.

When someone in a state of hyperarousal finally crashes into sleep, whether at night or during a daytime nap, that sleep tends to be lighter and less restorative than regular sleep. They might sleep for long periods, but never reach the deeper stages where the real restoration happens. So they wake up still tired, still needing more rest.

This pattern creates the appearance of excessive sleep need. The person spends 9 hours in bed at night and takes 90-minute naps during the day, totaling 10 or more hours of sleep. But because that sleep is fragmented and shallow due to underlying hyperarousal, it’s not actually meeting their body’s needs. They’re chronically under-rested despite sleeping more than most people.

Studies have linked this pattern to increased mortality risk, not because sleep itself is harmful but because the underlying hyperarousal is often connected to chronic stress, anxiety disorders, unresolved trauma, or other conditions that take a toll on overall health. Excessive sleep is the symptom, not the cause, of health problems.

What Short Naps Reveal

The finding that short naps of 30 minutes or less don’t carry the same health risks is revealing. Brief power naps work with the body’s natural ultradian rhythms rather than against them. They provide a quick restoration of alertness without dropping into deeper sleep stages that cause grogginess and sleep inertia upon waking.

People who naturally take short naps are often those whose nighttime sleep is basically good. They’re not desperately sleep-deprived. They’re using a nap strategically to boost afternoon performance, not as a desperate attempt to compensate for terrible nighttime sleep. This distinction matters enormously.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends limiting naps to 20 to 30 minutes in the early afternoon for this reason. A brief nap in this window can enhance alertness and performance without interfering with nighttime sleep. But this advice assumes the person is already getting adequate nighttime rest. For someone who’s chronically sleep-deprived or dealing with sleep disorders, a 20-minute nap barely touches the exhaustion they’re experiencing.

The Real Question: Why Are You Napping?

All of this research points to a more fundamental question than whether napping is good or bad. The question is: why does someone feel the need to nap in the first place?

If you’re napping because you stayed up late finishing a project and want a quick boost before an afternoon meeting, that’s one thing. If you’re napping because you literally cannot keep your eyes open despite getting what should be adequate nighttime sleep, that’s something entirely different.

The second scenario suggests problems that go beyond simple sleep scheduling. It points to either poor sleep quality, an undiagnosed sleep disorder, or some other health issue that’s causing excessive daytime sleepiness. The napping itself isn’t causing the health risks that appear in these extensive studies. It’s a marker for underlying problems that need attention.

People whose nap duration swings wildly from day to day tend to have worse health outcomes.

Addressing the Root Cause

Understanding napping as a symptom rather than a cause shifts how we should approach it. Telling someone who’s really exhausted to stop napping is like telling someone with a fever to stop sweating. You’re targeting the symptom while ignoring the actual problem.

The better approach is to ask what’s disrupting their sleep so badly that they need long daytime naps to function. For some people, the answer is sleep apnea or another sleep disorder that requires specific medical treatment. For others, it’s chronic pain that fragments sleep. For many, it’s hyperarousal rooted in stress, anxiety, or unresolved trauma.

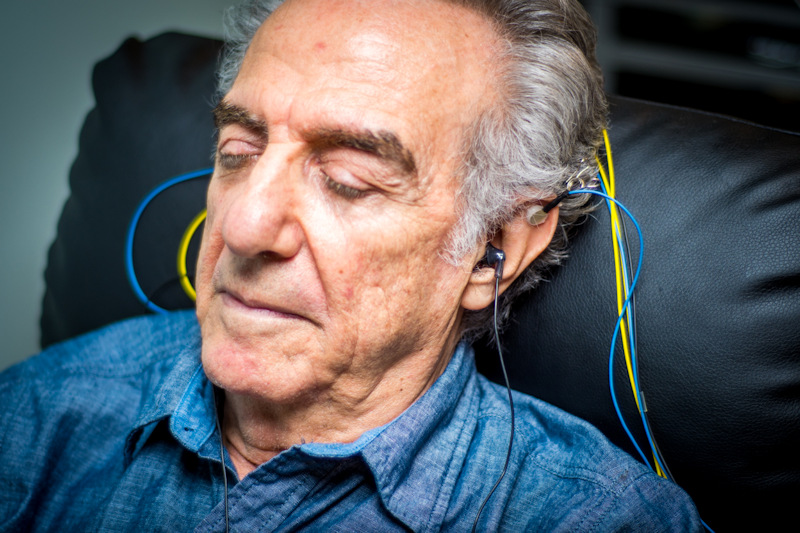

Sleep Recovery’s deep-brain anxiety protocol may have an answer when the underlying issue is a nervous system stuck in hyperarousal; surface-level interventions like sleep hygiene or even cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia often aren’t enough. The person can follow perfect sleep habits and still struggle because their brain isn’t downshifting into the calm state needed for deep, restorative sleep.

Brainwave entrainment works directly on the nervous system’s arousal level rather than just on sleep behaviors. By helping the brain access slower brainwave frequencies associated with deep relaxation and sleep, it addresses the hyperarousal that prevents truly restorative rest. Over time, as the nervous system learns to downshift more easily, both nighttime sleep quality improves and the desperate need for long daytime naps decreases.

The goal isn’t to eliminate napping. In some contexts and for some people, strategic short naps are genuinely beneficial. The goal is to resolve the underlying sleep disruption so that nighttime sleep becomes sufficiently restorative that the person wakes up actually refreshed rather than exhausted and needing long daytime sleep to compensate.

What This Means for You

If you’re someone who regularly needs long naps to get through the day, the research suggests you shouldn’t just accept this as usual. It’s worth investigating what’s happening with your nighttime sleep and why it’s not meeting your body’s needs.

Start by looking at the basics. Are you actually in bed long enough? Many people who complain of tiredness are simply not allocating enough time for sleep. If you’re only in bed six hours a night, daytime exhaustion isn’t surprising.

But if you’re spending adequate time in bed and still waking up tired and needing long naps, something else is going on. You may be waking frequently during the night without realizing it. You may not be reaching deep sleep stages. Your breathing may be disrupted. Your mind may be racing even while you’re technically asleep.

These are problems that have solutions, but you can’t solve them if you don’t recognize them as problems. Accepting chronic exhaustion and long daily naps as just how you are means missing an opportunity to address the underlying issue and potentially improve both your quality of life and your long-term health outcomes.

The emerging research on napping isn’t really about naps at all. It’s about sleep quality, nervous system regulation, and the subtle ways our bodies signal when something is off. Those long afternoon naps might be trying to tell you something important. The question is whether you’re listening.

For more information on Sleep Recovery’s programs, please visit https://sleeprecovery.net. Please call 1-800-927-2339 to schedule a no-cost phone consultation.