PTSD After Toxic Relationships: How the Mind and Brain Work Against the Sufferer

Rebecca sits alone in one corner of the bedroom, her heart racing against her ribs. Four years have passed since she left her emotionally abusive partner, yet her nervous system remains perpetually braced for danger. Sleep—once a refuge—has transformed into a battleground where fragments of psychological wounds resurface with unsettling clarity.

“I’m safe now,” she tries to reassure herself. “I’m safe.” But her body refuses to believe what her rational mind understands. This disconnect represents the central paradox of relationship-induced trauma: the continued neurobiological response to threats long after the actual danger has passed.

Rebecca’s experience mirrors thousands of survivors struggling with what researchers increasingly recognize as a distinct form of posttraumatic stress disorder—one born not from discrete catastrophic events but from sustained psychological injury within intimate relationships.

Relationship-induced PTSD operates through unique neural mechanisms, creating persistent alterations in brain function that standard therapeutic approaches often fail to address. Understanding these specific pathways offers new hope for the estimated 15-35% of people who develop diagnosable PTSD symptoms following psychologically abusive relationships.

The Invisible Wound: How Relationship Trauma Reshapes Neural Architecture

Dr. Christine Fennema-Notestine guides a patient through a brain imaging session at her neuroscience laboratory. The colorful display reveals a distinctive neural signature that Notestine has documented in hundreds of toxic relationship survivors.

“Notice the hyperactivation in the amygdala,” she points to an angry red cluster near the brain’s center. “Alongside reduced volume in the hippocampus and diminished activity in the prefrontal cortex. This change creates a perfect neurological storm—heightened threat detection with compromised emotional regulation and contextual processing.”

Unlike combat or disaster-related trauma, relationship-induced PTSD develops through prolonged exposure to unpredictable psychological danger from someone meant to provide safety and connection. This betrayal of attachment expectations creates distinctive neural adaptations.

“The brain’s attachment system becomes entangled with its threat detection system,” Notestine explains. “Normal relationship cues—even positive ones—can trigger cascades of stress hormones and defensive reactions. The neural networks meant to facilitate bonding become rewired to anticipate harm.”

These neurobiological changes help explain why survivors like Michelle Burundi, a 34-year-old architect, continue experiencing symptoms despite understanding their irrationality.

“I know in my logical mind my new partner isn’t going to explode over minor mistakes like my ex did,” Michelle shares. “But my body goes into panic mode anyway—racing heart, tunnel vision, that feeling of walking on eggshells—even when she’s just asking everyday questions.”

Functional MRI studies confirm her experience, showing that relationship trauma survivors process neutral social cues using brain regions typically reserved for threat assessment. The amygdala—the brain’s alarm system—activates in response to subtle triggers reminiscent of past relationship dynamics: certain tones of voice, specific phrases, or even particular facial expressions.

The heightened neural reactivity creates what neuroscientist Dr. Notestine terms “distress echoes”—physiological reverberations of past relationship trauma that continue long after the relationship ends.

Beyond “Just Get Over It”: The Neurobiological Reality

Popular culture often minimizes relationship trauma, suggesting survivors should simply “move on” or “let go” of past experiences. This advice fundamentally misunderstands the neurobiological nature of relationship-induced PTSD.

Regina M Sullivan, who specializes in the neurobiology of attachment trauma, explains this crucial distinction: “Telling someone to just get over a toxic relationship is like telling someone with a broken leg to just walk normally. We’re dealing with actual neural restructuring, not just painful memories.”

Brain imaging studies reveal specific structural changes in survivors of psychologically abusive relationships:

- Reduced gray matter volume in emotional regulation regions

- Altered connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex

- Dysregulated production of stress hormones that further damage brain tissue

- Disrupted function of the default mode network governing self-referential thought

These physical changes help explain persistent symptoms that defy rational control. When Melissa, a 41-year-old teacher who spent six years with a manipulative partner, describes feeling “rewired,” she’s not speaking metaphorically.

“My therapist showed me my brain scans,” Melissa explains. “She pointed to these overactive regions and said, ‘This is why you can’t just think your way out of your symptoms. Your brain is responding as it’s currently structured to respond.'”

This neurobiological perspective offers both validation and hope. Validation that symptoms represent fundamental physiological changes, not personal weakness. Hope because neuroscience increasingly demonstrates the brain’s remarkable capacity to reorganize through targeted interventions.

The Deception Detection System Gone Awry

Psychological abuse within relationships creates a particularly pernicious form of neural adaptation. The constant need to detect subtle signs of potential manipulation, gaslighting, or emotional attacks reconfigures the brain’s natural deception detection system.

The brain contains specialized networks for detecting social deception—a crucial evolutionary adaptation. In toxic relationships, these networks become hyperactivated through constant demand, eventually creating a default expectation of deception in all relationships.

This phenomenon explains why many survivors describe persistent trust issues that resist rational reassurance. Their brains have physically adapted to an environment where vigilance against deception is necessary for psychological survival.

Andrea, a 38-year-old attorney who left an emotionally abusive marriage two years ago, describes this persistent vigilance: “I analyze every conversation for hidden meanings or subtle put-downs. Someone can say something completely innocent, and my brain immediately looks for the trap, the double meaning, the setup for later criticism.”

This hyperactive detection of deception creates particular challenges for forming new relationships. Everyday interactions become minefields of potential triggers as the brain constantly scans for patterns resembling past manipulation.

“Healing requires not just processing what happened,” Santos emphasizes, “but retraining these hypervigilant neural networks to recognize safety as well as they currently recognize danger.”

Rebecca sits alone in one corner of the bedroom, her heart racing against her ribs. Four years have passed since she left her emotionally abusive partner, yet her nervous system remains perpetually braced for danger. Sleep—once a refuge—has transformed into a battleground where fragments of psychological wounds resurface with unsettling clarity.

“I’m safe now,” she tries to reassure herself. “I’m safe.” But her body refuses to believe what her rational mind understands. This disconnect represents the central paradox of relationship-induced trauma: the continued neurobiological response to threats long after the actual danger has passed.

Rebecca’s experience mirrors thousands of survivors struggling with what researchers increasingly recognize as a distinct form of posttraumatic stress disorder—one born not from discrete catastrophic events but from sustained psychological injury within intimate relationships.

Relationship-induced PTSD operates through unique neural mechanisms, creating persistent alterations in brain function that standard therapeutic approaches often fail to address. Understanding these specific pathways offers new hope for the estimated 15-35% of people who develop diagnosable PTSD symptoms following psychologically abusive relationships.

The Invisible Wound: How Relationship Trauma Reshapes Neural Architecture

Dr. Christine Fennema-Notestine guides a patient through a brain imaging session at her neuroscience laboratory. The colorful display reveals a distinctive neural signature that Notestine has documented in hundreds of toxic relationship survivors.

“Notice the hyperactivation in the amygdala,” she points to an angry red cluster near the brain’s center. “Alongside reduced volume in the hippocampus and diminished activity in the prefrontal cortex. This change creates a perfect neurological storm—heightened threat detection with compromised emotional regulation and contextual processing.”

Unlike combat or disaster-related trauma, relationship-induced PTSD develops through prolonged exposure to unpredictable psychological danger from someone meant to provide safety and connection. This betrayal of attachment expectations creates distinctive neural adaptations.

“The brain’s attachment system becomes entangled with its threat detection system,” Notestine explains. “Normal relationship cues—even positive ones—can trigger cascades of stress hormones and defensive reactions. The neural networks meant to facilitate bonding become rewired to anticipate harm.”

These neurobiological changes help explain why survivors like Michelle Burundi, a 34-year-old architect, continue experiencing symptoms despite understanding their irrationality.

“I know in my logical mind my new partner isn’t going to explode over minor mistakes like my ex did,” Michelle shares. “But my body goes into panic mode anyway—racing heart, tunnel vision, that feeling of walking on eggshells—even when she’s just asking everyday questions.”

Functional MRI studies confirm her experience, showing that relationship trauma survivors process neutral social cues using brain regions typically reserved for threat assessment. The amygdala—the brain’s alarm system—activates in response to subtle triggers reminiscent of past relationship dynamics: certain tones of voice, specific phrases, or even particular facial expressions.

The heightened neural reactivity creates what neuroscientist Dr. Notestine terms “distress echoes”—physiological reverberations of past relationship trauma that continue long after the relationship ends.

Beyond “Just Get Over It”: The Neurobiological Reality

Popular culture often minimizes relationship trauma, suggesting survivors should simply “move on” or “let go” of past experiences. This advice fundamentally misunderstands the neurobiological nature of relationship-induced PTSD.

Regina M Sullivan, who specializes in the neurobiology of attachment trauma, explains this crucial distinction: “Telling someone to just get over a toxic relationship is like telling someone with a broken leg to just walk normally. We’re dealing with actual neural restructuring, not just painful memories.”

Brain imaging studies reveal specific structural changes in survivors of psychologically abusive relationships:

- Reduced gray matter volume in emotional regulation regions

- Altered connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex

- Dysregulated production of stress hormones that further damage brain tissue

- Disrupted function of the default mode network governing self-referential thought

These physical changes help explain persistent symptoms that defy rational control. When Melissa, a 41-year-old teacher who spent six years with a manipulative partner, describes feeling “rewired,” she’s not speaking metaphorically.

“My therapist showed me my brain scans,” Melissa explains. “She pointed to these overactive regions and said, ‘This is why you can’t just think your way out of your symptoms. Your brain is responding as it’s currently structured to respond.'”

This neurobiological perspective offers both validation and hope. Validation that symptoms represent fundamental physiological changes, not personal weakness. Hope because neuroscience increasingly demonstrates the brain’s remarkable capacity to reorganize through targeted interventions.

The Deception Detection System Gone Awry

Psychological abuse within relationships creates a particularly pernicious form of neural adaptation. The constant need to detect subtle signs of potential manipulation, gaslighting, or emotional attacks reconfigures the brain’s natural deception detection system.

The brain contains specialized networks for detecting social deception—a crucial evolutionary adaptation. In toxic relationships, these networks become hyperactivated through constant demand, eventually creating a default expectation of deception in all relationships.

This phenomenon explains why many survivors describe persistent trust issues that resist rational reassurance. Their brains have physically adapted to an environment where vigilance against deception is necessary for psychological survival.

Andrea, a 38-year-old attorney who left an emotionally abusive marriage two years ago, describes this persistent vigilance: “I analyze every conversation for hidden meanings or subtle put-downs. Someone can say something completely innocent, and my brain immediately looks for the trap, the double meaning, the setup for later criticism.”

This hyperactive detection of deception creates particular challenges for forming new relationships. Everyday interactions become minefields of potential triggers as the brain constantly scans for patterns resembling past manipulation.

“Healing requires not just processing what happened,” Santos emphasizes, “but retraining these hypervigilant neural networks to recognize safety as well as they currently recognize danger.”

The Sleep-Trauma Connection: A Bidirectional Relationship

For relationship trauma survivors, sleep disruption emerges both as a primary symptom and a factor that maintains other symptoms. Research reveals a bidirectional relationship—trauma disrupts sleep and disrupted sleep prevents trauma resolution.

Rebecca’s nighttime awakenings represent a classic manifestation of how relationship trauma invades sleep architecture. During normal sleep, the brain cycles through distinct stages, each serving specific restorative functions. PTSD fragments these cycles, particularly disrupting REM sleep—the phase crucial for emotional processing.

“Think of REM sleep as the brain’s therapy session,” explains Dr. Elena Vasquez, director of the Traumatic Sleep Laboratory. “During this phase, the brain naturally processes emotional experiences while temporarily suppressing stress hormones. This neurological mechanism integrates traumatic memories without their full emotional charge”

When this natural processing fails, traumatic experiences remain fragmented and emotionally raw, fueling daytime symptoms. Research shows that relationship trauma survivors exhibit distinctive sleep disruptions:

- Reduced total sleep time despite subjective exhaustion

- Frequent micro-awakenings that fragment sleep cycles

- Diminished REM sleep quality with intrusion of stress hormones

- Alpha wave intrusions during delta wave sleep (indicating the brain remains partially alert during what should be deep sleep)

These disruptions help explain why many survivors report feeling chronically exhausted yet unable to achieve restorative sleep. Their brains never fully disengage from alert status, maintaining a level of vigilance incompatible with the vulnerability sleep requires.

This vigilance manifests as Jason’s persistent inability to fall asleep without elaborate safety measures. “I need specific conditions—door locked, phone nearby, night light on, background noise. Without these, my system won’t downregulate enough for sleep, even though the relationship ended three years ago.”

This sleep disruption creates a particularly troubling cycle. Sleep deprivation further impairs the prefrontal cortex’s regulatory function, intensifying daytime symptoms. These intensified symptoms increase stress levels, making sleep even more elusive the following night.

Breaking this cycle has emerged as a crucial intervention target. Promising research suggests normalizing sleep architecture can create cascading benefits across other symptom domains.

Sleep Recovery: Dual Neurofeedback for Healing the Traumatized Brain

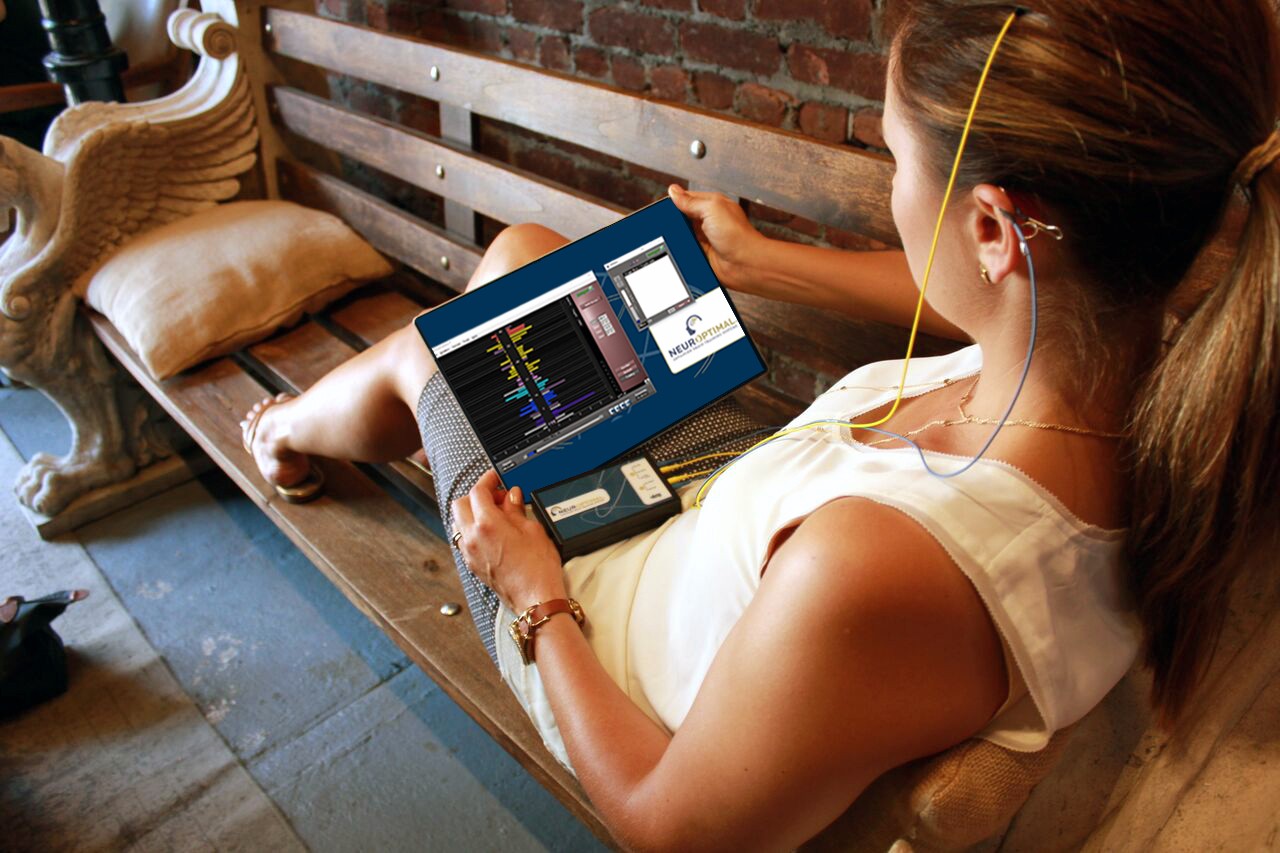

Among emerging treatments for relationship-induced PTSD, Sleep Recovery using specialized neurofeedback protocols shows particular promise, especially when implementing dual approaches that target both cortical stability and deeper trauma processing.

Dr. Nathan Reynolds, neuropsychologist and pioneer in trauma-focused neurofeedback explains the scientific rationale: “Relationship trauma creates dysregulation at multiple brain levels. Amplitude-based neurofeedback addresses outer cortical instability, while alpha-theta protocols target deeper subcortical networks maintaining maladaptive trauma responses.”

This dual approach works specifically to restore standard sleep architecture while simultaneously addressing daytime symptoms—a comprehensive intervention that recognizes the interconnected nature of trauma manifestations.

Amplitude-Based Neurofeedback: Stabilizing the Outer Brain

Relationship trauma creates distinctive disruptions in the brain’s cortical regions—typically excess high-beta activity (associated with hypervigilance) alongside deficient alpha waves (associated with calm, organized thinking).

“Think of it as an electrical storm in the outer brain,” Reynolds explains. “Sensors detect this chaotic activity in real-time, and through audio-visual feedback, train the brain to recognize and correct these imbalances.”

The process resembles a high-tech version of the children’s game “Hot and Cold.” When the brain produces more balanced activity—less high-beta and more alpha—it receives confirming feedback that gradually guides neural networks toward stability.

For Rebecca, amplitude training created noticeable changes within weeks: “First, I noticed I could sit quietly without scanning my environment constantly. Then, I started falling asleep more easily. Someone had finally located the dimmer switch for my overactive nervous system.”

This cortical stabilization creates the neurological foundation necessary for more profound healing work. When the outer brain regains regulatory capacity, inner trauma processing becomes possible without overwhelming the system.

Alpha-Theta Neurofeedback: Healing the Traumatized Inner Brain

While amplitude training stabilizes outer cortical regions, alpha-theta neurofeedback targets deeper subcortical networks where traumatic memories remain fragmented and emotionally charged.

“Alpha-theta training creates a unique brain state at the boundary between conscious awareness and subconscious processing,” explains Dr. Mira Desai, who specializes in this approach. “This theta-dominant state allows traumatic material to surface while maintaining enough alpha activity for emotional regulation—similar to during healthy REM sleep”

The protocol guides participants into deeper states, carefully monitoring the alpha and theta brainwave ratio. This process creates what researchers call a “trauma processing window” where the brain can access and reconsolidate traumatic memories without triggering overwhelming emotional responses.

Jason describes his experience during alpha-theta sessions: “I’d become aware of feelings or memories from the relationship, but they felt different—less immediate, more like watching a movie than reliving a nightmare. Sometimes, I’d have spontaneous insights about patterns I couldn’t see before.”

This reconsolidation process proves particularly valuable for relationship trauma, where gaslighting and manipulation often leave memories fragmented and contaminated with self-doubt. The alpha-theta state allows these memories to be accessed, organized, and stored with reduced emotional charge.

Restoring Natural Sleep Architecture

Perhaps most remarkably, this dual neurofeedback approach demonstrates particular effectiveness for sleep disruption—a notoriously treatment-resistant aspect of relationship-induced PTSD.

“Sleep architecture changes appear within the first month of treatment,” notes Reynolds. “Polysomnography shows normalization in sleep onset, reduced nighttime awakenings, increased REM quality, and most importantly, restoration of sleep’s natural processing functions.”

For Rebecca, these sleep improvements created ripple effects across her waking symptoms: “Once I started sleeping through the night, everything else began improving—my concentration returned, the emotional reactivity decreased, and most surprisingly, the constant sense of danger began fading.”

This sleep-mediated improvement pathway makes neurobiological sense. As sleep normalizes, the brain’s natural trauma processing mechanisms resume functioning, allowing gradual integration of relationship trauma without conscious effort.

A landmark 2022 study demonstrated that participants receiving combined amplitude and alpha-theta protocols showed significantly more improvement in relationship-specific PTSD symptoms compared to either protocol alone or traditional therapy approaches. Most importantly, these improvements persisted during 18-month follow-up assessments, suggesting fundamental neural reorganization rather than temporary symptom suppression.

Beyond Neurofeedback: Comprehensive Recovery Pathways

While neurofeedback approaches offer promising neurobiological interventions, most experts emphasize that complete recovery from relationship-induced PTSD benefits from integrated approaches addressing multiple dimensions of trauma.

Dr. Leila Kapoor, who directs an integrated trauma recovery program, describes their multi-level approach as follows: “We combine neurofeedback for neurobiological regulation, somatic therapies for embodied trauma, cognitive approaches for meaning-making, and carefully paced relational work to restore attachment security.”

This comprehensive model recognizes that relationship-induced PTSD affects interconnected systems that mutually reinforce each other. Neurobiological dysregulation maintains distorted cognitions; distorted cognitions perpetuate emotional wounding; emotional wounds manifest as somatic symptoms; and bodily distress signals trigger further neurobiological alarm.

Breaking this cycle requires coordinated intervention at multiple levels, with neurofeedback providing crucial support for the neurobiological foundation.

“The brain needs sufficient regulatory capacity before cognitive insights can be meaningfully integrated,” explains Kapoor. “Neurofeedback often creates the neurobiological stability necessary for other therapeutic approaches to work effectively”

This integrated approach proved transformative for Melissa: “The neurofeedback helped stabilize my system enough to use the other therapeutic tools. Before that, I intellectually understood concepts from therapy, but my body wouldn’t respond accordingly. The neurofeedback created a bridge between understanding and feeling different.”

The Future of Healing: Hope in Neuroplasticity

For the millions navigating the aftermath of toxic relationships, emerging neuroscience offers a fundamentally hopeful message: the same neuroplasticity that allowed trauma to reshape the brain also enables healing.

“The brain changes in response to traumatic and restorative experience,” emphasizes Dr. Desai. Relationship trauma creates maladaptive neural patterns through sustained negative experiences. Recovery occurs by providing the brain with sustained experiences of safety, regulation, and connection.”

This neuroplasticity principle transforms recovery from simply managing symptoms to actively restoring healthy neural function. Approaches like Sleep Recovery, which directly target dysregulated brain patterns, significantly advance this restoration-focused paradigm.

As Rebecca reflects, now able to sleep through most nights: “Understanding that my symptoms weren’t character flaws or permanent damage but adaptive responses that could be restabilized changed everything. My brain was doing what it evolved to do—protect me from danger. Now it’s learning that the danger has passed, and I can finally rest.”

For those still caught in the neurobiological aftermath of relationship trauma, this evolving science offers something beyond symptom management—the possibility of fundamental healing at the level where the injury occurred.

References:

- Psychobiology of Attachment and Trauma—Some General Remarks From a Clinical Perspective. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6920243/

-

Brain morphometry in female victims of intimate partner violence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12460692/

-

Article: ATTACHMENT, TRAUMA & NEUROSCIENCE by Cheryl Paulhus, Ed.D., LPC, CETP. https://traumaonline.net/attachment-trauma-neuroscience-cheryl-paulhus-ed-d-lpc-cetp/

-

Neurofeedback for posttraumatic stress disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and neurophysiological outcomes. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10515677/